I wrote an opinion piece in The Age newspaper this week called “Premier’s Reading Challenge no fun for kids who can’t read“, arguing we need to close the gap between research and practice in early literacy education, so more kids can enjoy, not dread, the Premier’s Reading Challenge.

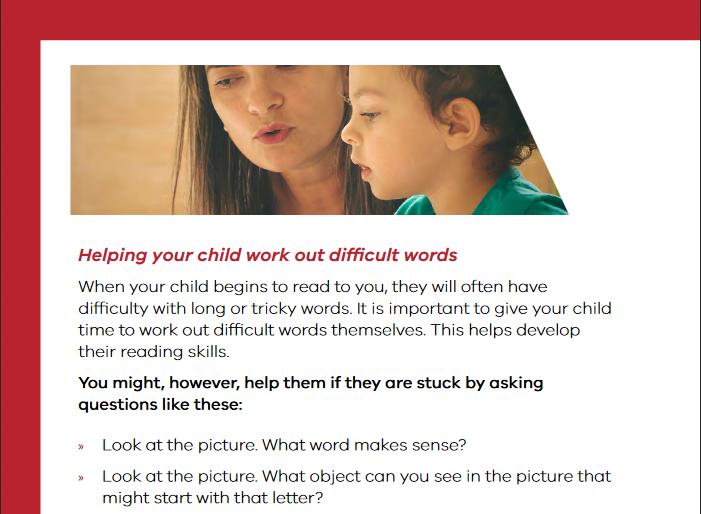

I hope it’s helped put another nail in the coffin of common, but extremely poor, literacy-teaching practices like rote wordlist-memorisation (the “magic words” etc) without regard to their structure, incidental-not-systematic phonics, and encouraging kids to guess words from first letter, sentence structure and context/pictures.

I hope it also helps kill off the idea that reading is natural, and replace educational blah-blah about reader identity and teacher literacy philosophy with more interesting discussions about what science tells us about how to best teach reading.

I’m sorry they didn’t include my link to Emily Hanford’s great “Hard Words: why aren’t kids being taught to read” audio documentary, but otherwise happy with it, especially the mention of David Kilpatrick’s seminar on 19 August at Melbourne Town Hall (have you signed up yet? He will also speak in Perth and Cairns, and Sydney and Adelaide, but they’re booked out).

Of course letters to the editor appeared the next day disagreeing with me. People who agree with something they read in the paper don’t generally rush to write to the editor. Editors don’t usually give a right of reply to these letters, so I’m giving myself one here.

A couple of the letters will have made many teachers cringe for their profession. Their authors seem blissfully unaware of the work of researchers like Marilyn Jager Adams, Stanislas Dehaene, Maryanne Wolf, Mark Seidenberg, Louisa Moats, David Kilpatrick, and Anne Castles, Kathleen Rastle and Kate Nation.

It’s kind of embarrassing that there are still teachers out there defending ideas and approaches reading researchers have long shown are bunkum. But here’s one letter:

Like a zombie that just won’t die, the common “three strategies” practice she describes (usually called the “three-cueing method” or “multicueing”) has no scientific basis. It’s a great way to teach the habits of weak readers, not strong readers.

It’s based on the always-dumb, half-baked idea that reading is a psycholinguistic guessing game, rather than a precise, skilled, learnt behaviour.

It’s hard to know what to say when someone succinctly describes something you’ve called poor practice, calls it “common practice” and then asserts that the poor practice you’ve described does not occur in schools. Since this letter was published on World Emoji Day, I think I’ll just say

Also (oh kill me with a spoon), a “digraph sound” is not a Thing. Can teachers of reading please be given a basic grasp of phonics terminology?

I checked the Premier’s Reading Challenge rules, and can’t find any mention of it being OK for kids to count books they’ve listened to someone else read, not read themselves. Maybe you can.

I hope what I write doesn’t just drive literacy teachers who aren’t interested in the science of reading to despair. I hope it drives them to retirement. People who aren’t interested in the science of teaching reading should not be teaching reading.

Here’s another letter from a Dr Jennie Duke of the Literacy Alliance Group. I have never heard of this group, so I googled it. Sadly, Google seems not to have heard of it either.

Dr Duke clearly hasn’t sat through a whole-school, waste-of-time Drop Everything And Read session during the Premier’s Reading Challenge as I have, watching kids pretend to read books that are simply too hard for them, to save face with their peers.

A third letter argues meaning comes first, and reading is “a naturally acquired acquisition”.

I’m not sure why the meaning-first brigade are so shy of asking kids to do important but hard work. As Stanislas Dehaene explained to us at the Language, Learning and Literacy conference earlier in the year, learning to read is at first very effortful, but if you don’t put in the effort to build the reading circuit linking vision and language in your brain, you’ll read poorly.

Building this reading circuit is a lot harder for some kids than others. Quality books, a smattering of phonics tricks and a focus on meaning are not going to cut it for the kids who currently inhabit the long tail of literacy under-achievement, and aren’t going to permanently arrest then reverse our medium-term measurable decline in reading standards.

Happily, we now seem to be getting a bit of leadership from the International Literacy Association regarding the place of systematic, explicit phonics in early literacy teaching. Here’s their 2019 brief on the topic, which asks:

I hope this leadership helps ALEA, PETAA and the AARE bloggers catch up.

Also, happily for me, the Age letters editor did publish a letter supporting my article:

Thanks, Jan!

I’ll give the last word to another letter submitted to the Age editor by Dr Tanya Serry of La Trobe University, but not published, which I think deserves wider circulation, and again my thanks:

Kate Finlay and Carol Marshall (letters 17 Jul 2019), in response to Alison Clarke’s previous letter, both describe ‘methods’ for reading instruction that do not align with the empirical evidence.

Goodman’s Psycholinguistic Guessing Game; which includes visual strategies among others, has long been discredited by advances in Cognitive Psychology research.

Systematic instruction in Phonics, as noted by Alison Clarke, essentially enables children to ‘crack the alphabetic code’ and is far more intellectually rigorous than teaching children ‘tricks’ with various letters of the alphabet.

Further, in support of Alison Clarke’s support for explicitly-taught systematic phonics, anyone who reads the scientific evidence on teaching children to read, will find clear statements that phonics alone will never be sufficient. It is now well-established that phonics must be embedded into a comprehensive program alongside instruction in phonemic awareness, reading fluency, vocabulary and oral language comprehension.

In light of the very recent ‘Short-Changed’ report by Buckingham and Meeks, who meticulously and objectively documented widespread shortcomings about the preparation of teachers to teach reading, we should all take heed of the vast amount of high-quality empirical research available to us all about how best to teach all children to read and to support those who struggle.

The post We need GOOD practice, not common practice appeared first on Spelfabet.

Follow

Follow

email

email